... a follow-up posting with a few more excerpts from the highly interesting chapter "fashion meets discretion" in the highly interesting book "design meets disability" ... excerpts that focus on the development of glasses from "medical necessity" to fashion statement and compare this trend with the status and stigma of hearing aids. Generally, the latter are "developed within a more traditional culture of design for disability". There are, however, some designers celebrating deafness by creating high fashion hearing aids, for instance here and here and here.

glasses

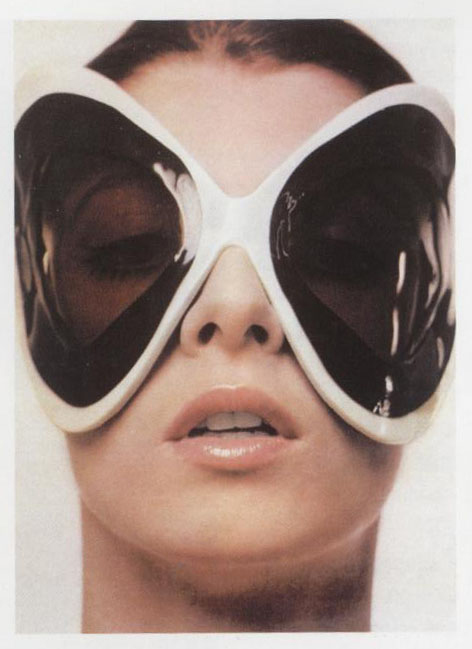

Glasses or spectacles are frequently held up as an exemplar of design for disability. the very fact that mild visual impairment is not commonly considered to be a disability, is taken as a sign o fthe success of eyeglasses. But this has not always been the case: Joanne Lewis has charted their progress from medical product to fashion accessory. In the 1930s in Britain, National Health Service spectacles were classified as medical appliances, and their wearers as patients. It was dictated that "medical products should not be styled." At that time, glasses were considered to cause social humiliation, yet the health service maintained that its glasses should not be "styled" but only "adquate". In the 1970s, the British Government acknowledged the importance of styling, but maintained a medical model for its own National Health Service spectacles in order to limit the demand. In the meantime, a few manufacturers were offering fashionable glasses to consumers who could afford them. As recently as 1991, the design press declared that "eyglasses have become stylish."

These days, fashionable glasses are available in the shopping mall or on Main Street. It has been reported that up to 20 percent of some brands of glasses are purchased with clear nonprescription lenses, so for these consumers at least wearing glasses has become an aspiration rather than a humiliation. So what lessons does this hold for design and disability? There are several, especially in relationship to the widely held belief that discretion is the ultimate priority in any design for disability.

First, glasses do not owe their acceptability to being invisible. Striking fashion frames are somehow less stigmatizing than the National Health Service's supposedly invisible pink plastic glasses prescribed to schoolgirls in the 1960s and 1970s. Attempting camouflage is not the best approach, and there is something undermining about invisibility that fails: a lack of self-confidence that can communicate an implied shame. (...)

But neither is the opposite true: glasses' acceptability does not come directly from the degree of their visibility either. Brightly colored frames exist, although they are still a minority taste. This might serve as a caution to medical engineering projects that have adopted bright color schmes for medical products "to make a fashion statement" as the automatic progression from making a product flesh-colored. Most spectacle design, and design in general, exists in the middle ground between these two approaches. This requires a far more skilled and subtle approach - one that is less easy to articulate than these extremes. (...) (Pullin, 2009:15-17)

(...) many fashion labels design and market eyewear collections. Collections, labels, and brands: these words set up different expectations and engagement from consumers. And consumers is a long way from patients or even users. (...)

Eyewear designers Graham Cutler and Tony Gross have spent thirty years on the front lines of the revolution that turned eyewear "from medical necessity into key fashion accessory." It is interesting to note how recent this revolution was, given how much it is now taken for granted. (...), and their customer base transcends age and occupation.

(...) Certainly, fashion designers are rarely part of teams even developing wearable medical products, which is incredible considering the specialist skills they could bring as well as their experience and sensibilities. But if we are serious about emulating the success of spectacle design in other ares, we need to involve fashion designers, inviting them to bring fashion culture with them.

hearing aids

Compare glasses with hearing aids, devices developed within a more traditional culture of design for disability where discretion is still very much seen as the priority. Discretion is achieved through concealment, through a constant technological miniaturization. The evolution of the hearing aid is a succession of invisible devices: objects hidden under the clothing, in the pocket, behind the ear, in the ear, or within the ear. As the hearing aid has grown ever smaller, it has occasionally broken cover only to migrate from one hiding place to another. What has remained the same is the priority of concealment.

Such miniaturization has involved amazing technological development, but it is not without a price. (...) hearing aids' performance is still compromised by their small size and (...) they could deliver better quality sound if they weren't so constrained. This is how fundamental the priority of discretion can be. Yet for many hearing-impaired people, their inability to hear clearly is far more socially isolating than the presence of their hearing aid. (...) (Pullin, 2009)

- - - - - - - -

- Pullin, G. (2009). design meets disability. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press.

- image (Pierre Cardin) via