"Jamaica is a small country of less than 3 million people that has been fundamentally shaped by European imperialism. I’m from a Black-majority society, though as with many other Caribbean and Latin countries, the racial/color conventions are different from the United States. The “one-drop rule” doesn’t hold, and “browns” were originally clearly demarcated from “Blacks” in a three-tiered white/Brown/Black social pyramid. As a “brown” Jamaican, I was — and to a certain extent still am — relatively privileged vis-à-vis the Black majority. So in a sense, in coming to the U.S. to work after I got my PhD in Canada, I was changing race, becoming part of an unambiguously subordinated “Black” American racial group, while equipped with the inherited cultural capital and privilege of my “brown” Jamaican middle-class origins and education.

You’ll appreciate, then, the complexities of this evolving hybrid combination of privilege and disadvantage, insider and outsider status, and its resulting weird epistemic amalgam of insight and obtuseness. I’m not Black American in the sense of having U.S. family origins that go back to slavery. But I’m Black and an American citizen, and I certainly identify with and have tried to support in my work, the long Black American struggle for racial equality and justice.

The U.S. and Jamaica are vastly different in innumerable ways. But what they have in common is that they’re both former slave societies, built on the racial exploitation of African persons. Yet whereas this historical reality is very much part of everyday consciousness in Black-majority Jamaica, it has been suppressed in white-majority America. Hence the hostility to the “1619 Project” and the truths it’s telling, truths that many white Americans still refuse to hear."

- - - - - - - -

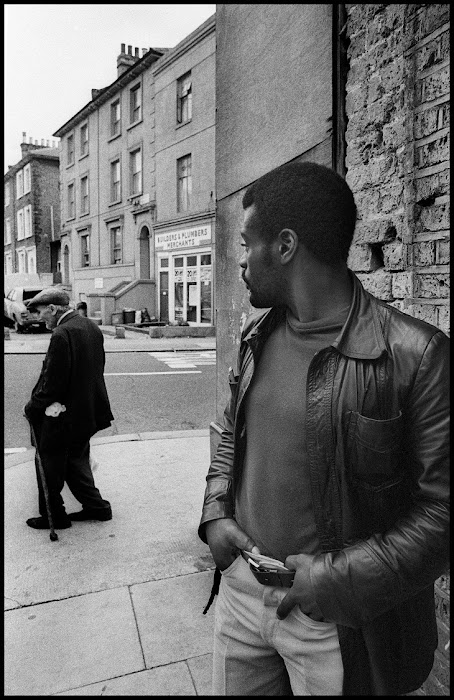

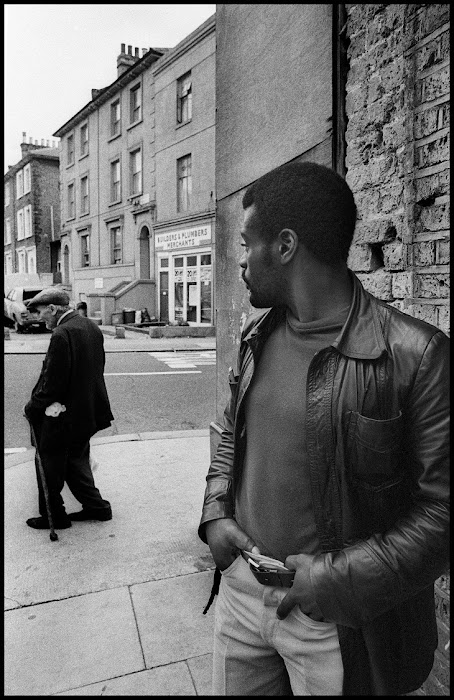

photograph by Adrian Boot (Railton Road, Brixton, 1979, home of Race Today, a British political magazine quoted as "the leading organ of Black politics")

via

Thanks!!

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for dropping by and leaving a comment, Kenneth!

Delete